Fur Trading on the Detroit River

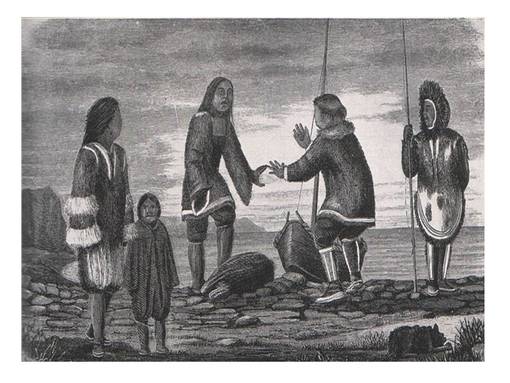

Fur Trading - Wikimedia Commons

by Kathy Warnes

French voyageurs paddled down the river that they called “De Troit,” meaning the strait or the narrows. The French voyageurs who dipped their paddles smoothly in and out of its blue sunlit waters were the first non-natives to navigate the Detroit River and land on Detroit shores.

The Iroquois and the Dutch are Allies

The French came to trade furs and explore, but others had more sinister reasons to explore the Detroit River. The river and its adjacent lands crossed the warpath of the Iroquois, fierce warriors from the east. By the 1600s, the Iroquois had allied with the Dutch who had founded New Amsterdam. The Dutch bought furs from the Iroquois and shipped the furs on sailing ships to Europe to be used for hats, cloaks, and ornaments.

The beaver in what is now New York had been nearly all trapped by the middle of the Seventeenth Century, and the Iroquois ranged westward. They wiped out most of the Huron who shared their land with the Algonquin tribes called the Ottawa and Chippewa. The English arrived in New York, supplanting the Dutch, but maintaining the Dutch friendships with the Iroquois and giving them access to Lake Erie and the other Great Lakes. The French had established themselves in Montreal and the French voyageurs explored the vast forests to the west of the newly founded cities in Quebec.

Father de Casson Lands on the Detroit River

Traveling in Indian fashion, the voyageurs proclaimed their joy of life and the wilderness in exuberant songs as they paddled their way to the trading posts and towns. They could only transport furs and trading goods by water because there were no roads for horses and wagons. Father Dollier de Casson, the first priest to stand on the Michigan shore of the Detroit River, was a French nobleman who after a notable military career became a priest and explorer.

In 1670, he landed on the left bank of the River in what is now Detroit, somewhere between the mouth of the Rouge River and Fort Wayne. Father de Casson planted a large wooden cross covered with the French coat of arms on the site, prophetically demolishing a stone figure that the Indians worshipped. Then he continued on to Sault Ste. Marie, to serve a mission there.

The French and English Vie for Control of the Fur Trade

The French and the fur trade produced the first sailing ship on the Upper Great Lakes as well. The Griffon left Niagara in 1679, with Robert Cavelier LaSalle and a French and Native American contingent on board, including Father Louis Hennepin. La Salle hoped to use his advantage of being the first ship to travel the Detroit River to win a fur trade monopoly. The French and English along with a few soldiers and land seekers from the Thirteen Seaboard colonies began to congregate in Detroit.

By the end of the Seventeenth Century the French and English were jostling each other for control of the fur trade and the allegiance of the Indians. The Iroquois, still aligned with the English, had invaded French territory and the commander of the French fort at Michilimackinac vowed to protect French interests in Michigan. In Albany, the English offered better prices for pelts and enjoyed a shipping advantage because of their access to New York harbor through the Hudson River.

The French had only the St. Lawrence River to gain their shipping ports and the St. Lawrence season was so short that the French ships could make only a yearly voyage from Montreal up the Ottawa River across Lake Nipissing and the Georgian Bay and into the Great Lakes. The Ottawa River route to Detroit began in Montreal, passed over about thirty portages, and came down through Georgian Bay through Lake Huron to Detroit. The Niagara route over Lakes Ontario and Erie was shorter and contained one portage at Niagara Falls.

Clarence Burton Collects Fur Trading Contracts

Capitalistic fur traders in Montreal fitted out canoe loads of merchandise and sent them to the upper country under the care of a trustworthy voyageur, or if the load warranted, an expedition of voyageurs. After the canoe or canoes were loaded, agreements or contracts were negotiated with the required number of men to make the voyage. All of these agreements and contracts were written and notarized in Montreal. The men who could write signed their names to the agreements, and if they were illiterate, that fact was noted in the contract.

The notaries kept these contracts which provide valuable primary sources of early fur trading transactions. Detroit historian Clarence Burton collected what he estimated to be thousands of contracts and agreements, dating from 1680-1760, containing the names of the early voyageurs, where they lived, their occupations, dates of their visits to the western country, and times and terms of employment. Frequently these contracts show the values of services and commodities and the volume of the trade.

The North West Company and the Ottawa Route

In 1798, the North West or Canada Company controlled most of the fur trade between Montreal and Lake Superior. The North West Company had been organized in the winter of 1783-1784, but had never become an incorporated company like its chief rivals, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the American Fur Company. The North West resembled a modern holding company, consisting chiefly of Montreal firms and partnerships in the fur trade.

The North West Company began during the American Revolution and in 1811 it temporary merged with the American Fur Company. In 1816, it established its posts over much of Canada and the northern United States. Its main line of communication was the difficult canoe route from Montreal up the Ottawa River, and through Lake Huron and Lake Superior to its chief inland depot, Grand Portage before 1804 and Fort William after 1804. In 1821, the North West Company merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

All too soon, the day of the free trader depending on his own resources had virtually passed into history. Only a few fur traders filed applications at Mackinaw to be free traders. The North West Company included all Indian trappers and traders and was practically free from serious competition at this time.

Dr. Charles L. Codding described a trip with the voyageurs in about the year 1800, using the Ottawa Route. The journey began about nine miles outside of Montreal on the St. Lawrence at La Chine. A guide responsible for all pillage and loss and having sole control of the fleet directed a birch bark brigade of three or more canoes. All of the men and their wages were answerable to him and he decided the times and places of the arrivals and departures of the fleet. When fur trader Antoinie de Mothe Cadillac journeyed from Canada to establish the French Fort at Detroit, he followed the Ottawa Route.

Great Lakes Fur Trader Pierre Leblanc and His Conflicting Worlds

For two centuries, British and French fur traders vie for territory and influence with Great Lakes Native Americans, clashing and combining cultures.

When the first French fur trading voyageurs exchanged greetings and goods with welcoming Native Americans they changed history, as did the first English trader who stood in the door of his rough, wooden cabin and held out trinkets to the Indians. As historian Richard White phrased it: “…When they (the Algonquian Indians) accepted European goods and gave furs in return, a still emerging market system in Europe impinged on their lives…”

British and French Fur Traders Compete for Indian Allies

White argued that the Algonquian Indians in the Detroit and Great Lakes region obtained religious, political, and social benefits from European goods even though they as individuals did not accumulate wealth. He pointed out that the nature of the French fur trade also differed from that of the British. According to White, the French fur trade was a combination of entrepreneurial traders, merchant financiers, licensed monopolists, and government regulators, and the French instituted the custom of relying on the Huron or Wyandot and Ottawa Indians to act as middlemen and expeditors of the trade.

The British, playing a commercial hand, shaped the fur trade as a weapon of war in the fierce struggle for dominance of the North American Continent. They cleverly played their commercial cards in the Detroit and continental fur trade by portraying themselves not as conquerors but as friends bringing gifts and trade goods. They usually offered better terms than the French and high quality goods at low prices, and basically won the commercial war before the advent of the military war.

In the meantime, the Native Americans were the middlemen and in a good negotiating position with most of their cultures still intact. In 1755, many Frenchmen felt that the fur trade of the Great Lakes did not earn even one percent of the price it had cost the King, and they would have allowed the entire trade to go to the English if the English had agreed to acknowledge French boundaries along the Ohio River. Both sides were courting the Indians with goods and promises and the Algonquians reaped the benefits of both while their preexisting native technologies survived for a long time alongside the new technologies that trade goods introduced.

Pierre LeBlanc, Fur Trader

Individual fur traders like Pierre LeBlanc were as instrumental as Native Americans in establishing fur trading regions and without premeditation, transforming the cultures of both French and Indian worlds. Leblanc, who would later settle in Ecorse, a small settlement about eight miles from Detroit, was one of the first French men to travel to the area, arriving in 1790 for the Hudson Bay Company.

Fur trading comprised most of the business in this western country at this time and created Native American, French, and British capitalists. Hunting fur bearing animals like beaver and muskrat, preparing their furs for market and transporting them to Montreal provided much of the impetus for exploration and settlement along the Detroit and Ecorse Rivers.

Trade was carried on between Montreal and the upper country by canoes and bateaux. Canoes loaded at Montreal were brought to Detroit either over the Ottawa River coming down through Georgian Bay or through the Niagara route over Lakes Ontario and Erie. The Niagara Route was easier because it had one portage at Niagara Falls while the Ottawa route had at least 30 portages.

Pierre LeBlanc Blends Cultures

Since French and other white women were scarce in this frontier settlement, Pierre married a Fox Indian woman and established a homestead farm on what is now West Jefferson Avenue near the Detroit River. When a French trapper took an Indian wife, his marriage helped him survive Native American attacks or other trouble with the warriors still numerous in the Downriver area. The LeBlancs established themselves as sturdy farmers and trappers, trading with the Indians and maintaining a good relationship with them.

Pierre and his Indian wife had a son whom they named Pierre, who was born in 1820 in a log house on the old family farm. This log house served as a place of worship for the early Catholics and for many years Mass was said within its rustic walls. Early in his life, the second Pierre revealed his sturdy French stock and Indian blood. He was a constable when he was only twenty years old and for many years he was a highway commissioner, laying out many of the first roads in the southeastern part of Michigan.

Pierre Le Blanc Pays his Taxes

In 1850, the LeBlancs built a new house to replace the old log cabin and Pierre’s son, Frank Xavier LeBlanc, was born in that house. Through his years of growing up on the LeBlanc farm near the Detroit River, Frank X. collected many souvenirs of his family’s early days in Ecorse and Downriver.

Peter Godfroy, a merchant, survived the Indian massacre at Frenchtown in Monroe in which the entire garrison and all the settlers within the fort except him were tomahawked. He gave Frank X. LeBlanc’s grandfather Pierre a receipt for goods that he had purchased and although yellowed and faded it was still legible. Another of his valuable possessions was a tax statement that the sheriff of Wayne County had sent Pierre LeBlanc in July 1824. The statement requested that LeBlanc pay the $2.03 he owed in taxes!

Individual fur traders like Pierre LeBlanc brought about a blending or exchanging of Native American and white culture and the transformation of both.

References

Burton, C.M., Cadillac’s Village or “Detroit Under Cadillac,” with a List of Property Owners and a History of the Settlement,” 1701 to 1710, Detroit, 1896

LaForest, Thomas and Saintonge, Jacques, Our French-Canadian Ancestors, Palm Harbor, Florida, 1993.

Morgan, Lewis Henry, The League of the Iroquois, North Dighton, Massachusetts: J.G. Press, 1995

Murphy, Lucy Eldersveld, A Gathering of Rivers: Indians, Metis, and Mining in the Western Great Lakes, 1737-1832. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000

Smith-Sleeper, Susan, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounters in the Western Great Lakes, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

White, Richard, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great lakes Region, 1650-1815, Cambridge University Press, 1997

“Catholic Masses Said in Log Cabin of LeBlanc,” Ecorse Advertiser, June 6, 1950

“An Old Time Trip with the Voyageurs: An Interesting Account of Transportation of Furs from the Northwest by Way of the Ottawa River One Hundred Years Ago,” Dr. Charles Codding, Duluth Evening Herald, April 7, 1900.

French voyageurs paddled down the river that they called “De Troit,” meaning the strait or the narrows. The French voyageurs who dipped their paddles smoothly in and out of its blue sunlit waters were the first non-natives to navigate the Detroit River and land on Detroit shores.

The Iroquois and the Dutch are Allies

The French came to trade furs and explore, but others had more sinister reasons to explore the Detroit River. The river and its adjacent lands crossed the warpath of the Iroquois, fierce warriors from the east. By the 1600s, the Iroquois had allied with the Dutch who had founded New Amsterdam. The Dutch bought furs from the Iroquois and shipped the furs on sailing ships to Europe to be used for hats, cloaks, and ornaments.

The beaver in what is now New York had been nearly all trapped by the middle of the Seventeenth Century, and the Iroquois ranged westward. They wiped out most of the Huron who shared their land with the Algonquin tribes called the Ottawa and Chippewa. The English arrived in New York, supplanting the Dutch, but maintaining the Dutch friendships with the Iroquois and giving them access to Lake Erie and the other Great Lakes. The French had established themselves in Montreal and the French voyageurs explored the vast forests to the west of the newly founded cities in Quebec.

Father de Casson Lands on the Detroit River

Traveling in Indian fashion, the voyageurs proclaimed their joy of life and the wilderness in exuberant songs as they paddled their way to the trading posts and towns. They could only transport furs and trading goods by water because there were no roads for horses and wagons. Father Dollier de Casson, the first priest to stand on the Michigan shore of the Detroit River, was a French nobleman who after a notable military career became a priest and explorer.

In 1670, he landed on the left bank of the River in what is now Detroit, somewhere between the mouth of the Rouge River and Fort Wayne. Father de Casson planted a large wooden cross covered with the French coat of arms on the site, prophetically demolishing a stone figure that the Indians worshipped. Then he continued on to Sault Ste. Marie, to serve a mission there.

The French and English Vie for Control of the Fur Trade

The French and the fur trade produced the first sailing ship on the Upper Great Lakes as well. The Griffon left Niagara in 1679, with Robert Cavelier LaSalle and a French and Native American contingent on board, including Father Louis Hennepin. La Salle hoped to use his advantage of being the first ship to travel the Detroit River to win a fur trade monopoly. The French and English along with a few soldiers and land seekers from the Thirteen Seaboard colonies began to congregate in Detroit.

By the end of the Seventeenth Century the French and English were jostling each other for control of the fur trade and the allegiance of the Indians. The Iroquois, still aligned with the English, had invaded French territory and the commander of the French fort at Michilimackinac vowed to protect French interests in Michigan. In Albany, the English offered better prices for pelts and enjoyed a shipping advantage because of their access to New York harbor through the Hudson River.

The French had only the St. Lawrence River to gain their shipping ports and the St. Lawrence season was so short that the French ships could make only a yearly voyage from Montreal up the Ottawa River across Lake Nipissing and the Georgian Bay and into the Great Lakes. The Ottawa River route to Detroit began in Montreal, passed over about thirty portages, and came down through Georgian Bay through Lake Huron to Detroit. The Niagara route over Lakes Ontario and Erie was shorter and contained one portage at Niagara Falls.

Clarence Burton Collects Fur Trading Contracts

Capitalistic fur traders in Montreal fitted out canoe loads of merchandise and sent them to the upper country under the care of a trustworthy voyageur, or if the load warranted, an expedition of voyageurs. After the canoe or canoes were loaded, agreements or contracts were negotiated with the required number of men to make the voyage. All of these agreements and contracts were written and notarized in Montreal. The men who could write signed their names to the agreements, and if they were illiterate, that fact was noted in the contract.

The notaries kept these contracts which provide valuable primary sources of early fur trading transactions. Detroit historian Clarence Burton collected what he estimated to be thousands of contracts and agreements, dating from 1680-1760, containing the names of the early voyageurs, where they lived, their occupations, dates of their visits to the western country, and times and terms of employment. Frequently these contracts show the values of services and commodities and the volume of the trade.

The North West Company and the Ottawa Route

In 1798, the North West or Canada Company controlled most of the fur trade between Montreal and Lake Superior. The North West Company had been organized in the winter of 1783-1784, but had never become an incorporated company like its chief rivals, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the American Fur Company. The North West resembled a modern holding company, consisting chiefly of Montreal firms and partnerships in the fur trade.

The North West Company began during the American Revolution and in 1811 it temporary merged with the American Fur Company. In 1816, it established its posts over much of Canada and the northern United States. Its main line of communication was the difficult canoe route from Montreal up the Ottawa River, and through Lake Huron and Lake Superior to its chief inland depot, Grand Portage before 1804 and Fort William after 1804. In 1821, the North West Company merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

All too soon, the day of the free trader depending on his own resources had virtually passed into history. Only a few fur traders filed applications at Mackinaw to be free traders. The North West Company included all Indian trappers and traders and was practically free from serious competition at this time.

Dr. Charles L. Codding described a trip with the voyageurs in about the year 1800, using the Ottawa Route. The journey began about nine miles outside of Montreal on the St. Lawrence at La Chine. A guide responsible for all pillage and loss and having sole control of the fleet directed a birch bark brigade of three or more canoes. All of the men and their wages were answerable to him and he decided the times and places of the arrivals and departures of the fleet. When fur trader Antoinie de Mothe Cadillac journeyed from Canada to establish the French Fort at Detroit, he followed the Ottawa Route.

Great Lakes Fur Trader Pierre Leblanc and His Conflicting Worlds

For two centuries, British and French fur traders vie for territory and influence with Great Lakes Native Americans, clashing and combining cultures.

When the first French fur trading voyageurs exchanged greetings and goods with welcoming Native Americans they changed history, as did the first English trader who stood in the door of his rough, wooden cabin and held out trinkets to the Indians. As historian Richard White phrased it: “…When they (the Algonquian Indians) accepted European goods and gave furs in return, a still emerging market system in Europe impinged on their lives…”

British and French Fur Traders Compete for Indian Allies

White argued that the Algonquian Indians in the Detroit and Great Lakes region obtained religious, political, and social benefits from European goods even though they as individuals did not accumulate wealth. He pointed out that the nature of the French fur trade also differed from that of the British. According to White, the French fur trade was a combination of entrepreneurial traders, merchant financiers, licensed monopolists, and government regulators, and the French instituted the custom of relying on the Huron or Wyandot and Ottawa Indians to act as middlemen and expeditors of the trade.

The British, playing a commercial hand, shaped the fur trade as a weapon of war in the fierce struggle for dominance of the North American Continent. They cleverly played their commercial cards in the Detroit and continental fur trade by portraying themselves not as conquerors but as friends bringing gifts and trade goods. They usually offered better terms than the French and high quality goods at low prices, and basically won the commercial war before the advent of the military war.

In the meantime, the Native Americans were the middlemen and in a good negotiating position with most of their cultures still intact. In 1755, many Frenchmen felt that the fur trade of the Great Lakes did not earn even one percent of the price it had cost the King, and they would have allowed the entire trade to go to the English if the English had agreed to acknowledge French boundaries along the Ohio River. Both sides were courting the Indians with goods and promises and the Algonquians reaped the benefits of both while their preexisting native technologies survived for a long time alongside the new technologies that trade goods introduced.

Pierre LeBlanc, Fur Trader

Individual fur traders like Pierre LeBlanc were as instrumental as Native Americans in establishing fur trading regions and without premeditation, transforming the cultures of both French and Indian worlds. Leblanc, who would later settle in Ecorse, a small settlement about eight miles from Detroit, was one of the first French men to travel to the area, arriving in 1790 for the Hudson Bay Company.

Fur trading comprised most of the business in this western country at this time and created Native American, French, and British capitalists. Hunting fur bearing animals like beaver and muskrat, preparing their furs for market and transporting them to Montreal provided much of the impetus for exploration and settlement along the Detroit and Ecorse Rivers.

Trade was carried on between Montreal and the upper country by canoes and bateaux. Canoes loaded at Montreal were brought to Detroit either over the Ottawa River coming down through Georgian Bay or through the Niagara route over Lakes Ontario and Erie. The Niagara Route was easier because it had one portage at Niagara Falls while the Ottawa route had at least 30 portages.

Pierre LeBlanc Blends Cultures

Since French and other white women were scarce in this frontier settlement, Pierre married a Fox Indian woman and established a homestead farm on what is now West Jefferson Avenue near the Detroit River. When a French trapper took an Indian wife, his marriage helped him survive Native American attacks or other trouble with the warriors still numerous in the Downriver area. The LeBlancs established themselves as sturdy farmers and trappers, trading with the Indians and maintaining a good relationship with them.

Pierre and his Indian wife had a son whom they named Pierre, who was born in 1820 in a log house on the old family farm. This log house served as a place of worship for the early Catholics and for many years Mass was said within its rustic walls. Early in his life, the second Pierre revealed his sturdy French stock and Indian blood. He was a constable when he was only twenty years old and for many years he was a highway commissioner, laying out many of the first roads in the southeastern part of Michigan.

Pierre Le Blanc Pays his Taxes

In 1850, the LeBlancs built a new house to replace the old log cabin and Pierre’s son, Frank Xavier LeBlanc, was born in that house. Through his years of growing up on the LeBlanc farm near the Detroit River, Frank X. collected many souvenirs of his family’s early days in Ecorse and Downriver.

Peter Godfroy, a merchant, survived the Indian massacre at Frenchtown in Monroe in which the entire garrison and all the settlers within the fort except him were tomahawked. He gave Frank X. LeBlanc’s grandfather Pierre a receipt for goods that he had purchased and although yellowed and faded it was still legible. Another of his valuable possessions was a tax statement that the sheriff of Wayne County had sent Pierre LeBlanc in July 1824. The statement requested that LeBlanc pay the $2.03 he owed in taxes!

Individual fur traders like Pierre LeBlanc brought about a blending or exchanging of Native American and white culture and the transformation of both.

References

Burton, C.M., Cadillac’s Village or “Detroit Under Cadillac,” with a List of Property Owners and a History of the Settlement,” 1701 to 1710, Detroit, 1896

LaForest, Thomas and Saintonge, Jacques, Our French-Canadian Ancestors, Palm Harbor, Florida, 1993.

Morgan, Lewis Henry, The League of the Iroquois, North Dighton, Massachusetts: J.G. Press, 1995

Murphy, Lucy Eldersveld, A Gathering of Rivers: Indians, Metis, and Mining in the Western Great Lakes, 1737-1832. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000

Smith-Sleeper, Susan, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounters in the Western Great Lakes, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

White, Richard, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great lakes Region, 1650-1815, Cambridge University Press, 1997

“Catholic Masses Said in Log Cabin of LeBlanc,” Ecorse Advertiser, June 6, 1950

“An Old Time Trip with the Voyageurs: An Interesting Account of Transportation of Furs from the Northwest by Way of the Ottawa River One Hundred Years Ago,” Dr. Charles Codding, Duluth Evening Herald, April 7, 1900.